Written by Robert Pool, Ph.D.

Everyone has heard of Malcolm Gladwell’s 10,000-hour rule: You need 10,000 hours of practice to become an expert at anything. It’s pretty intimidating if you stop to think about it. That’s 4 hours a day, 20 hours a week, 1,000 hours a year—for 10 years. Who has that sort of time? I don’t. You probably don’t either.

On the other hand, best-selling author Josh Kaufman published a book a few years back that promises you can “learn anything” in just 20 hours. Not 20 hours a week for 10 years, or even 20 hours a week for 1 year. Just 20 hours total. You’ve got 20 hours, right?

And what’s really interesting is that both of these claims—Gladwell’s 10,000-hour rule and Kaufman’s 20 hours—are talking about exactly the same thing: deliberate practice. We’ll talk more about that in a minute.

But first: Which claim is right? Is it 10,000 hours or 20 hours? Strangely enough, as long as you interpret the two claims correctly, they are both right. What’s more, once you understand what is going on, you are left with a blueprint for how you, or anyone, can excel in most areas of business and life—without devoting your entire life to it.

Here’s how to understand the two very different claims: The 10,000-hour rule is true for the top performers in a field where there is intense competition and training. Think of concert pianists, chess grandmasters, and prima ballerinas. These people truly do put in thousands—or tens of thousands—of hours of practice to get to the top because that’s what their competition is doing. Every world-class concert pianist has practiced for 10,000 hours or more— usually much more. If you want to excel in one of these areas, to be among the best in the world, you have to start young and devote much of your life to becoming great.

Kaufman is talking about something else altogether. Say that you’ve always wanted to ride a unicycle (or speak French or play the ukulele), but you’ve never tried. His point is that with the right sort of practice, 20 hours is enough to get you to a point where you at least won’t embarrass yourself. You won’t be great, but you’ll be doing well enough to get some satisfaction out of it and maybe even impress your friends.

What these two theories have in common is both involve a very powerful approach to training called “deliberate practice.” It is the single best way to get better at something—anything, really—as proven by many years of scientific research. Briefly, deliberate practice involves picking out specific aspects of the skill you wish to improve, doing exercises designed specifically to improve those aspects, getting feedback on your performance, using that feedback to guide further practice, then repeating.

Kaufman’s big idea is to take this powerful training method that classical musicians, chess masters, Olympic gymnasts, and the like use to hone their world-class skills and use it instead when you are first getting started learning something—in the “first 20 hours,” as the title of his book says. Of course, it is not as easy as it sounds. The classical musicians and Olympic athletes who use it in their training have spent years perfecting their deliberate practice techniques, and there is no way a beginner in a field can match their training proficiency. Still, even if it is carried out imperfectly, deliberate practice is so much more effective than the unstructured way most people go about learning something new that the results can seem like magic. For a beginner, 20 hours of deliberate practice is enough to make a huge difference.

So Kaufman is on to something. If you want to learn to play the ukulele or take up wind surfing, try deliberate practice for 20 hours. You’ll be surprised by how quickly you pick it up.

There is a much more powerful message here, and it is aimed at the rest of us—not the rank beginners or those at the very top of their field, but the ones who are just doing okay. Most of us settle into comfortable ruts in our jobs, our leisure activities, and our lives in general. We get to a point where we’re “good enough,” and we coast. We’re not like classical violinists or grandmasters, devoting hours a day to deliberate practice, working hard to get better. Quite frankly, we don’t have to because our peers—the people we’re competing against for jobs and promotions and bonuses—aren’t practicing for several hours a day either. For the most part, they’re just like us—they’ve learned just enough to do the job reasonably well and are coasting, not really getting much better as time goes on.

So imagine what would happen if we got out of our comfortable ruts and applied Kaufman’s “20 hours” to our daily jobs. If 20 hours of deliberate practice can take you from never having wind-surfed to skimming handily over the waves or from not knowing the difference between your sombrero and your cabeza to carrying on a conversation in Spanish, what might it do for your job performance?

It can make a huge difference. Think of it in tennis terms. Suppose you’re a weekend tennis player. You learned enough to serve and return balls, and you and your friends enjoy your friendly games even though none of you are more than just okay. After 10 years of playing weekly, you’re not much better than you were when you started because, let’s face it, you’ve never really tried very hard to get better, and just playing the same way every week does nothing to improve your game.

Now let’s suppose you got inspired by watching Serena Williams in a Grand Slam finals, and you decide you want to get serious. You hire a tennis instructor who says ‘let’s work on your crosscourt forehand’ and for the next ten weeks you spend a couple of hours each weekend focused on just that. Instruction, practice, feedback, repeat.

At the end of those 20 hours, you’re not ready to take on Roger Federer, but you have a new, improved skill that lifts you above the people you’ve been playing with. Your cross-court forehand is a weapon that wins you an extra point or two each game, and now suddenly you’re the best player in your group of friends. It feels good, and now, invigorated, you decide you’re going to spend another 20 hours of deliberate practice on your backhand. And then your serve. And so on . . . .

Now suppose instead of tennis you decide to spend 20 hours of deliberate practice on getting better at your job. You pick out one aspect that could use improvement that will make a difference in your overall performance, and you work on it. You get ideas for practice techniques from a mentor or a more accomplished peer, or maybe you figure out some exercises yourself. The key is to have a clear idea of the skill you’re trying to develop, specific exercises aimed at improving that skill, regular feedback on how you’re doing, and the ability to shape your training in response to the feedback. At the end of the 20 hours, you will see a big improvement. In particular, you will now have an advantage over anyone who has not made this effort.

You see, people’s performance in the business world is much closer to how you and your friends play tennis on the weekend than it is to how Serena Williams and Roger Federer play tennis—people in the business world are not spending hours deliberately practicing, working to improve their skills. In fact, most people in the business world spend almost no time on improving specific skills. They get to a level of acceptable performance and coast, often with the vague assumption that they’ll get better with experience. But they don’t. Research shows that just going in and doing your job every day does very little to help you improve. The only way to see serious improvement is through deliberate practice.

So here is the takeaway message: You can see a surprisingly large improvement in your performance—in your job, in your sports activities, in pretty much anything you do—with a relatively small investment in time. It won’t work if you’re in a highly competitive field where people are spending hours a day on practice—classical music, pro sports, and so on—but those are the exceptions rather than the rule. In most areas of life people just don’t work that hard to get better, and you can set yourself apart by being one of the few who do. I’m not saying it’s easy. Deliberate practice requires thought, focus, and effort, but you’ll be surprised at what you can do with a commitment of just a few hours a week.

There is a young man in California named Max Deutsch who in successive months taught himself to draw a realistic self portrait, solve a Rubik’s cube in under 20 seconds, land a standing back flip, play an improvised blues guitar solo, and hold a conversation in Hebrew. Now, he wasn’t starting from scratch on every one of these skills, nonetheless over the course of a month he was able to develop a striking new skill—month after month.

Deliberate practice opens the door. All you have to do is walk through.

About the Author

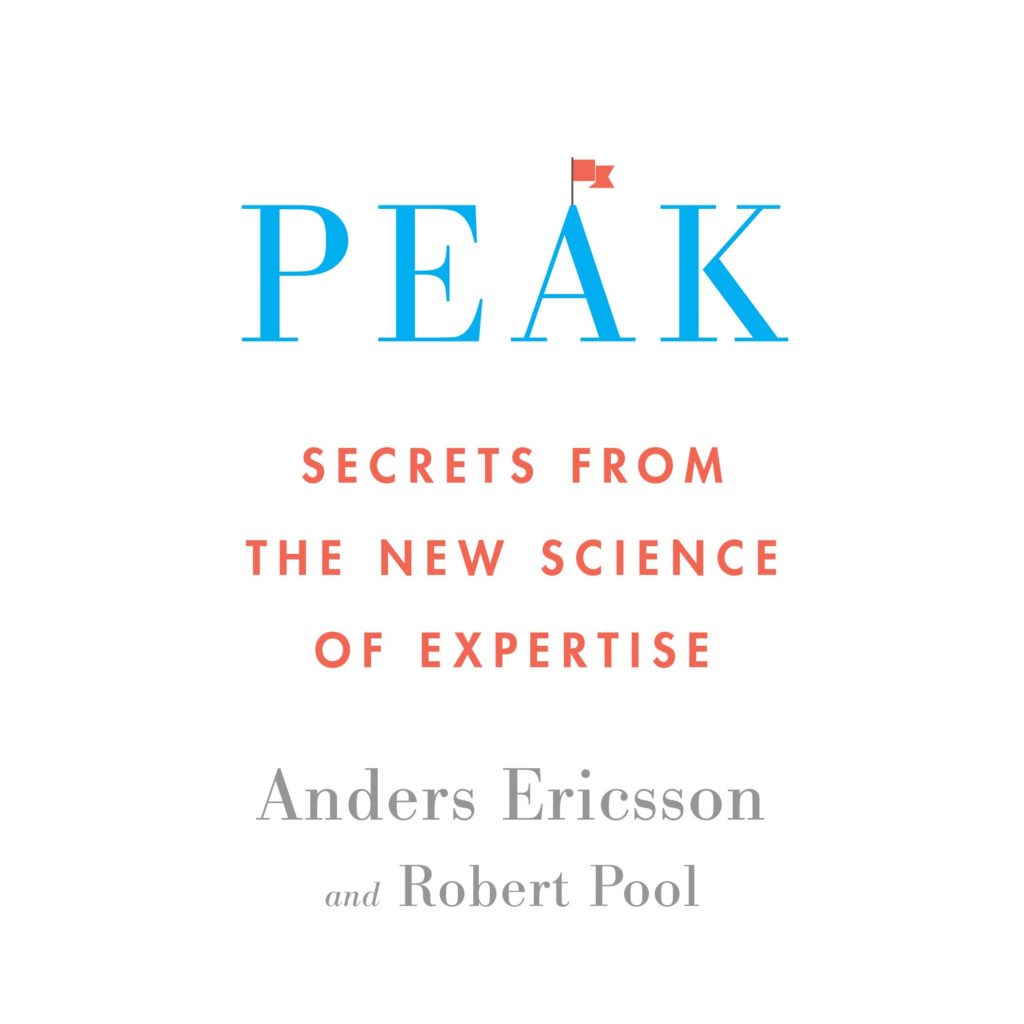

Robert Pool, Ph.D., is a writer, speaker, and consultant specializing in deliberate practice and it application. His most recent book, co-written with Anders Ericsson, is Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise.